Archive

Level Design Nostalgia – It’s Lying To You

It’s been a good long while since my last post, but something stuck in my craw recently, so here we go. Let’s talk about video game level design and the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia.

There’s an image that’s been floating around the intertubes for a while now:

On the left is the map for E1M6 of Doom, “Central Processing”. On the left is a hyperbolic representation of the linearity and cutscene-abundance of a modern FPS.

For a lot of gamers, particularly those of the Doom generation, this seems like really trenchant criticism. Look, it says: back in the day levels were these sprawling, free-roaming, multi-path masterpieces of clever design! Now everything is a linear march from point A to B, stopping only to have a cutscene! To be fair, if you were a Doom player back in the day, it’s easy to understand why you might have that impression. But is it true?

I gave it away in the post title, of course. No, it is not true. That map looks nice and complicated and multi-path, but it’s a clever deception. And the line diagram on the right looks terribly linear and boring, but it’s also a clever deception. The first and most obvious reason is that if you took a top-down screenshot of a modern FPS level from within its own editor (which is, essentially, how the Doom map image is produced), it would look several orders of magnitude more complicated than the Doom map. The real question is: what is the actual gameplay? What is the flow? Because in the end, a level design in an FPS is a path, a flow – it is the creation of a course for the player to follow from a start point to an end. It may branch to multiple endings, it may branch but merge again later on, but it is fundamentally a decision about player movement through the level.

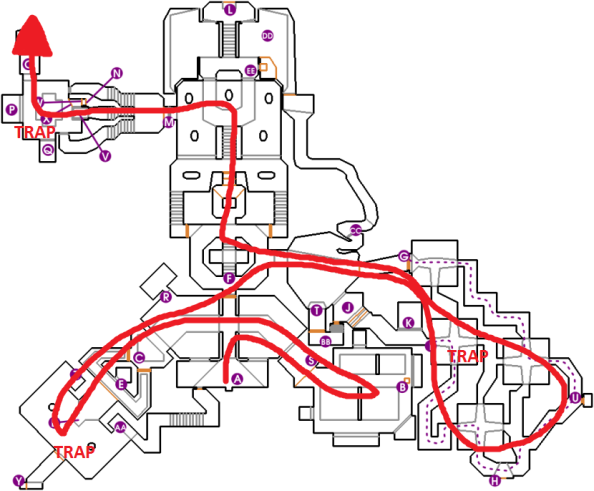

Let’s look at E1M6 again.

Examined in a bit more detail, we can start to notice some things. It’s really broken into only a few discrete sections which have limited, often single-path connections to each other. Now, unless you know which doors open in which direction, etc., you can’t really make a definitive statement as to how many paths there are. But it is nonetheless immediately obvious that, for example, the entire upper-left wing is a discrete unit, the central area is similarly discrete, the lower left, and so on. Given that that’s true, it means that these are places you at best go into and then backtrack out of – essentially dead ends or U-turns.

Next we have to remember that Doom’s gameplay was, aside from the shooting, simply a matter of finding a colored keycard to open a door of the same color so that you can find another colored keycard to open the next door. This was mandatory, it was true in every level, and (with damn few exceptions) there was no way around it. If the developers had designed the level so that you had to get the red card to get the yellow card to get the blue card to get to the exit, that was what you did. Which means the levels, by dint of this one fact, must be linear. Appearance of the map notwithstanding, if you had to follow a specific and breadcrumbed path to reach the exit, you’re walking a line.

With the help of a Doom wiki to know where the keys and doors are, we can even plot this:

Yes, I know I didn’t follow the corridors exactly, but that’s sort of my point. Those places where you could go down one of two staircases and the like don’t represent real path branches – they all go to the same places and it doesn’t really impact the gameplay at all. That maze on the right? It’s not really multiple paths – you must end up at a certain location to hit a switch, so the “maze” has no dead ends -just a series of loops that all go to the same place. So when we map out the actual critical path of player movment, it’s “north, go right, go back left, go back right, loop through the maze, go back to the center, go north, hang left, exit.” There are no actual branches of gamplay, no alternative routes longer than a staircase. It’s a straight line that doubles back on itself a few times.

You’ll also see where I marked “Trap”. This was Doom’s THING, man. You walked into a room, the door closed behind you, and a closet opened up and a monster popped out. Every. Damn. Time. It was so ubiquitous that people referred to the technique as “monster closets” and poked fun at iD’s apparent dependence on them to generate scares. They were predictable as hell after a while: you knew, for example, that when you found a key, picking up the key probably was going to open a monster closet.

So, if E1M6 is actually a linear path, what does it look like if we do like the creators of our original image did with their modern FPS “example” and abstract it down to just the player’s simplified movement flow:

Wait. Wait a second! That’s BASICALLY THE SAME DAMN THING. Only with monster closets instead of cutscenes.

You might say this was a long way to go to “disprove” what amounts to a bit of internet trolling. I argue, however, that it’s important as a game designer or even as a critic (amateur or otherwise) of games to have a clear perception of what’s really happening when you play a game – when you experience a piece of level design. And it is equally important to understand that our perceptions of what old-school games were like are often as inaccurate as all our other memories – colored by nostalgia, viewed through the vaseline-coated lens of the emotional experience of the time more than with an accurate perception. Doom’s actually a terrific example for this, being as it is so deeply ingrained in the PC-gamer nerd psyche. For example, you probably think of it as an FPS, but in terms of gameplay mechanics it’s probably understood just as well as a Robotron clone played from the first person. This extends beyond video games into all forms of gaming. D&D grognards will swear up and down that 4E has basically done away with all the role-playing elements of the game, without ever noticing that there were often never rules for the things they are complaining are missing. They will moan bitterly that the focus on use of a map and minis has turned the game into a board game of resource management, while simultaneously A) forgetting that D&D was originally a miniatures game, and B) happily insisting on the importance of encumbrance rules and endlessly tweaking combinations of items, skills, and classes to justify some exploit.

The simple truth is that the more things change, the more they stay the same. And when you are looking at the dominant beasts in a field (FPS video games, D&D as an RPG), nostalgia is always convincing you the earlier versions were so much more creative and robust than they actually turn out to have been.